Residual or soil applied (ie. preemergent or PRE) herbicides can provide many benefits to weed managers. In contrast to foliar-applied (postemergent) herbicides that only affect the weeds present at the time of the application, residual herbicides persist in the soil and have activity on weeds that germinate after the application. Depending on the chemistry of the specific herbicide, the rate applied, weed spectrum in the field, and environmental conditions, weed control may last for several weeks or months.

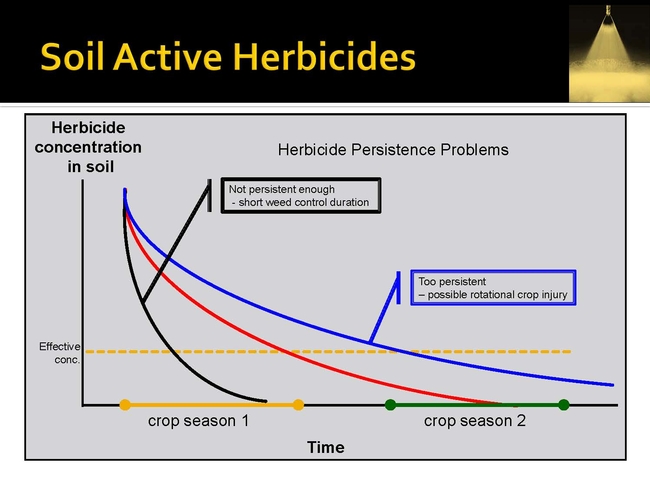

When performance problems arise with residual herbicides, they usually take the form of either unexpectedly short or unexpectedly long residual activity. As illustrated in the line diagram below, our goal with residual herbicides is to apply a sufficient rate of the product to keep the concentration in soil above some threshold level (the yellow dashed line) during the growing season (the specific level varies among specific herbicide/weed/environment situations).

Ideally, the herbicide will last through enough of the season to minimize weed competition with our crop and then dissipate to biological inactive levels (and eventually complete degradation) (red line). Shorter than expected activity can lead to poor weed control later in the season and require additional action and expense by the weed manager to supplement weed control (the black line). Residual activity that is longer than expected can lead to problems with injury to a subsequently planted rotational crop (the blue line).

If you are concerned about whether the herbicide you (or a previous weed manager) used previously will be safe on your rotational crop, conducting a "bioassay" may be worth your time. A bioassay (biological assay or assessment) is a simple and inexpensive way to determine if biologically active levels of a herbicide are present. I've attached a publication from the Alberta Research Council that I stumbled upon online outlining how to conduct a bioassay. In it's most basic form, you can take soil from your area in question, and plant a few crop seeds and observe their growth response for a few weeks. If the seedlings emerge and grow normally, it may be safe to replant. You should compare it to similar soil that is known to be "clean" so that you can separate herbicidal effects from other factors.

The most direct and obvious seed to use in the bioassay is the crop you are considering planting in the field. If you want to know if it's safe to plant lettuce, test it with lettuce - makes sense right? However, you could also test with a species that is known to be very sensitive to the herbicide (sort of a "canary in the coal mine" strategy).

The most sensitive species will vary with the specific herbicide in question. One way to make an educated guess at a good indicator species is to look at the herbicide label and look for "rotation crop restrictions" or "plantback restrictions" - if you see that the label says not to plant a certain crop for a long interval, that might be a good indicator for your assay. Similarly, if the label indicates that a certain weed is well controlled by that herbicide, that weed or a related crop might make a good bioassay indicator species.

When used according to label directions soil residual herbicides usually work just as intended and are safe for subsequently planted crops. However, occasionally an application error, unusual weather conditions, or an especially sensitive rotational crop can be affected by the herbicide. Using a bioassay is a low cost and simple way to get a good idea about whether it is safe to plant a sensitive crop in a field that has been treated with a residual herbicide.

Take care,

Brad

Attached Files: